By Kendra Chatburn; cover photo courtesy of SmithGroup

Universities are finding ways to advance their mission, bring in revenue, and transform their campuses by partnering with companies, investors, and developers in a variety of ways. One such example is the Science, Technology, and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus development at the University of Delaware (UD). It is a property ripe with opportunities for public-private partnerships (P3s), and it is transforming the UD campus and surrounding region.

The 272-acre development will be a dense, live-work-learn community on UD land. It is owned by 1743 LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of UD, and will include a multitude of projects aligned with the University’s research and educational mission. Across STAR Campus, there are a variety of ownership models—with some projects owned by private-sector partners and other projects owned by the university. We recently sat with two of the visionaries guiding STAR Campus growth to learn more:

- Peter Krawchyk, AIA, AUA, LEED-AP, UD’s Vice President of Facilities, Real Estate, and Auxiliary Services and University Architect

- Tracy Shickel, UD’s Director of Economic Development

STAR Campus is an innovation community. What, exactly, does that mean?

Shickel: An innovation community is an inclusive and diverse group of collaborators, each with its own interests, but all focused on core research or innovation areas. We collaborate around moving that innovation forward. Some collaborators bring money, some skills and expertise, some time, some knowledge, but all are aligned around the importance of the core innovation, and all are additive to progressing that innovation or research.

Krawchyk: We specifically don’t call it a research park because it’s more than just research. Plus a research park shuts down at 5 o’clock. We want live-work-learn. We want transit-oriented. We want to support multi-generational housing.

On that note, what does UD hope to achieve at STAR Campus?

Krawchyk: We hope to achieve a 24/7/365 live-work-learn type of development that supports, enhances, and leverages the research capabilities of the university. The other real goal is the economic development of the state. The site was previously a Chrysler plant, so there were a lot of blue collar jobs lost in 2008, which was a huge blow to the city. UD purchased this land in 2009, and we’re looking at ways to bring jobs—a different spectrum of jobs—back. Those jobs can range from biopharmaceutical manufacturing to energy to pure research. We’re also talking about having a hotel / conference center. So it’s about synergies of the entire university with industry. And it’s about kick starting a homegrown industry.

Shickel: Based on our estimates given the current pipeline of projects, we will have created as many new jobs at STAR Campus by the first quarter of 2020 as Chrysler employed at its peak. So STAR Campus is important to economic development. It’s exciting for the community and the State, and it’s necessary for the region.

As for what it all looks like, we are really focusing in on growing an interdisciplinary innovation community aligned with the university’s core research competencies—delivering transformational research that has the potential to change society. We’re not real estate developers. This is not a real estate play. UD’s mission is education and research. So any prospective project that goes onto STAR Campus must be a collaborative research effort with the university, and must offer students experiential learning and employment opportunities. It’s about innovation that helps students and the community be their best selves, learn, and perform at their best.

An example of experiential learning is that our hospitality business management program will run the new hotel that Peter mentioned. We’ll partner with a hotel brand and developers to deliver the facility, and then super-charge the project by integrating our students.

STAR is an example of transit-oriented development. Can you talk about the role of transit in this project, and how transit is supporting STAR’s goals?

Shickel: The goal is for people to be able to easily go to and from campus, receive services and education, and engage with students, so we’re enhancing our accessibility—including mass transit access. We’re on I-95 and sit on an Amtrak corridor and the SEPTA line, and also the university and City are working together on more bike infrastructure.

As part of transit access, there will be a new regional transportation center walkable to campus—so, a new station with new track infrastructure. It’s a $50 Million investment that includes ADA accessibility. Plus MARC (commuter rail service in Maryland and Washington, DC) may potentially come to Newark. This development will be transformational, and ultimately, any way you want to get here, you can. The only thing we don’t have is a helipad (yet)!

On the note of parking, though, it’s just not what planners and students want to see. So how do you build inclusiveness and accessibility? We’ve really had to think strategically about these issues.

Krawchyk: To me the biggest piece is the train station. It’s a real key, as we’re on the east coast corridor. Once the train comes here, it’s just 90 minutes in either direction to get to NY or DC—without having to pay NY or DC rent. So we want to attract people not just locally, but regionally. We also hope to attract people internationally.

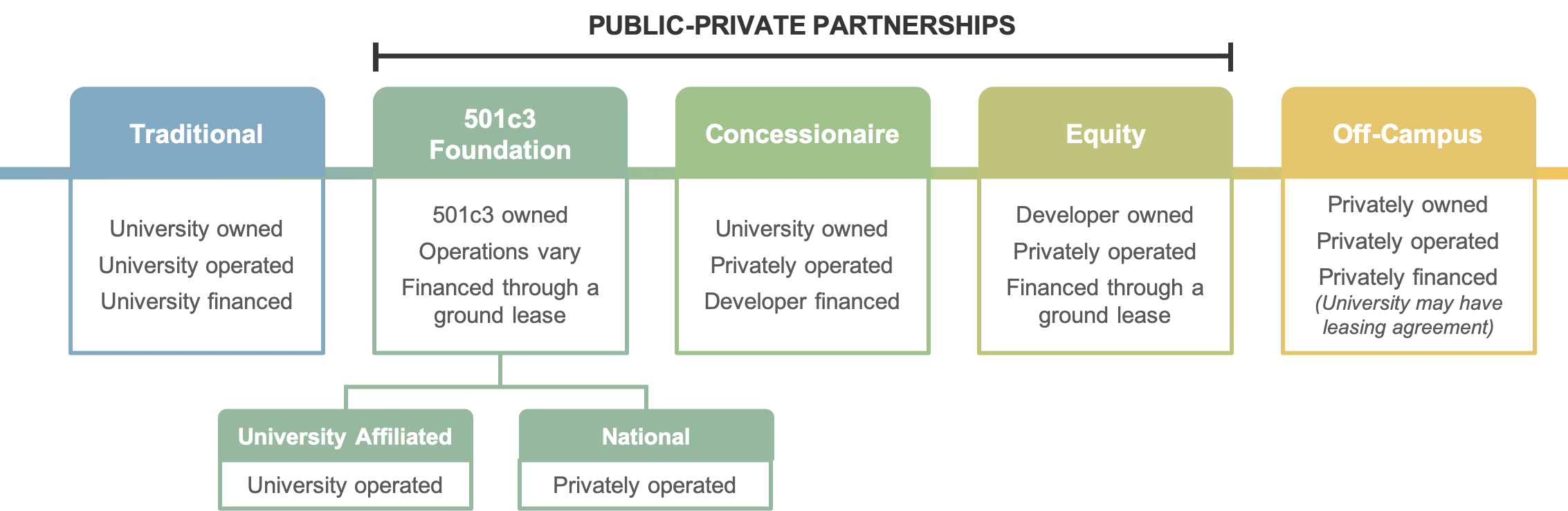

STAR Campus is a great model of a university partnering with private-sector and nonprofit organizations. Can you talk a bit about these partnerships in terms of the spectrum of deal structures—from traditional self-financed and developed projects to off-campus projects? Where is STAR Campus along this spectrum?

Shickel: We have diverse models along the public-private continuum. The Carol Ammon and Marie Pinizzotto M.D. Biopharmaceutical Innovation Building currently under construction is a traditional university-owned project. However, the STAR Campus Health Sciences Complex is owned by a developer—Delle Donne & Associates. The Chemours Discovery Hub (research and development facility) is a different model. Bloom Energy (energy/power generation systems partnership) is yet another completely different model. Different collaborators and projects have different needs. The commonality is physical proximity to UD and access to talent.

Krawchyk: The reason to be all over the spectrum is that we recognize some things shouldn’t be our core business, so a blend of financing makes sense. We just appreciate that the adjacency and geography sets us up for opportunities.

Here’s a concrete example of a current potential P3: Our president has set a goal to increase our graduate population over the next several years. We have about 3,300 students currently, and we want to grow to about 6,000. Right now, we have about 60 beds for graduate students, but a lot of these students are international. So if someone comes from China, where do they find a place to live? We recognize that graduate housing is, therefore, something we should really look at. And that’s probably a good P3 because it goes into a market that could be apartments, and it’s a project at a different level than a typical residence hall. Here the value of the P3 is not financial, it is instead the expertise brought by the development team to tailor the building design and operations within a specific market.

P3s are not inherently “the answer,” though. We think a lot about what our goals are, and what we’re willing to give up. Depending on a project’s attributes, it can be much easier to not do a P3.

What do developers and other partners make of all these opportunities to collaborate? How are you engaging with them?

Shickel: We’ve seen a lot of proactive interest from

developers and investors. We work with them individually, bringing them into conversations with university faculty and researchers to see what makes sense from a collaboration perspective. If a developer says, “I want to do housing,” what does that mean? Is the project addressing the needs of our undergraduate students? Graduate students? The market? How do we partner with that developer or investor so the project is aligned with the university’s mission? So we’re very collaboration-oriented, not transaction-oriented. We also have people who are very competent with the transactional pieces internally at UD, for example on the real estate side, but my role is truly to build and foster those partnerships and help with progressing and aligning the various parties.

On a completely separate note, STAR Campus has been designated an IRS Opportunity Zone. This is a federal economic incentive for redevelopment. We are one of the few transit-oriented Tier 1 research institutions with land, and it’s a way for investors to reduce or eliminate federal capital gains; this makes us highly interesting to investors. That doesn’t mean we’re open to anything—if you want to come in here and build a retail strip mall, that’s not a fit. But we have some very robust opportunities with some of our programs to do creative projects.

What is STAR Campus doing that is different?

Shickel: Something we’re doing that’s very unique is we’re mixing up innovation community stakeholders within the same building. That’s very uncommon. Usually a company will build a building and there’s no one else in there but them. In the STAR Campus Health Sciences Complex, for example, you can walk down the Translation Hallway to see into active research labs on one side, and community-accessible health services and clinics on the other. At the north end of the Translation Hallway, there is the Go Baby Go Café, which raises funds for research on rehabilitation and independent mobility, and shows off a ground-breaking harness enabling victims of brain injury to gain physical and social mobility as employees. On the south end of the hallway, there is a mix of private industry companies along with non-profit DTP@STAR’s wet lab incubator startup companies that focus on cancer therapeutics, biotechnology, advanced materials, chemical separations, photonics, and more. We don’t have this mix in every building on STAR Campus, but we have it in a few places as a purposeful attempt to try to get these people to collide with each other and continue to innovate. So, we’re taking opportunities through our planning process to ensure diverse stakeholders have the opportunity to meet, convene, and talk.

What would you tell higher ed administrators on other campuses who are reading this piece?

Krawchyk: Stick to your values and be patient. Try to gain as much experience as you can in this type of effort, as it’s completely outside of what many, if not most, universities are used to. At this point, it’s something almost all universities are trying to do, but we’re not as good yet as the private side. So, don’t hesitate to ask for help—advisors can be key.

Shickel: Two things. First, stick to your mission. Take the time to engage numerous stakeholders and have conversations that help you build a model that you can be proud of, that’s self-sustaining. What we’re about is educating and fostering research that changes society, so we know we really need to work with partners and collaborators who are aligned with that.

Second, think not only about how to bring industry to students, but how to bring students to industry. STAR Campus, for example, is very closely aligned with the career services function of the university. And we try to make sure there are ample internship, co-op, and employment opportunities—from undergrad to grad to postdocs. Beyond the obvious internships with partners, we also have grad students doing market research for us right now on workforce development in key industries. That’s grad students learning while helping us understand market needs and trends. Other services are available: Partners can use university catering services with students, or print services with students.

And what would you tell developers or other potential partners?

Shickel: Developers need to be fully aware of what they’re committing to, and need to truly be collaboration-oriented. There are a lot of developers who are interested in contributing to the development of STAR Campus, but might be more transaction-focused. The way that UD approaches P3 collaboration is not short-term, and is about relationship building. Partners on projects like these must also be aligned with the school’s / project’s mission. Finally, we work from a long-term ground lease model, which means developers really have to be committed to working from a ground lease perspective. With all of those pieces combined, this model is not for everybody and that’s fine. It’s about being honest and transparent at the beginning, and knowing what we’re all signing up for. At the end of the day, we are here because we’re committed to student learning and research.

When working with academic institutions, prospective collaborators should also be aware that we don’t move as quickly as they’re accustomed to in the private sector. We tend to go slowly and more deliberately. There’s a lot of interaction with students, faculty, researchers, government leaders; this engagement and alignment takes longer to do. We also want to partner with organizations committed to higher ed. It’s okay to have investment goals, but our mission is education. So, partners need to ask themselves, “Is that something I want to sign up for? Is this a nuisance for me, or an important part of my business model?” The reality is, not every project is a good fit for us.

Finally, think about how you can be additive. It can be easier for a developer to be additive to something we’re already invested in or a core competence.

PETER KRAWCHYK, Vice President for Facilities, Real Estate

Previously, Krawchyk has served as the University Architect and Director of Planning and Project Delivery since July 2015. Earlier he was the University Architect and Campus Planner from 2012-15 and Director of Facilities Planning and Construction from 2010-12. Before that, Krawchyk served as a Senior Associate at Ayers Saint Gross from 2008-10 and as Associate Director of Facilities Planning and Construction at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1998-2008. He earned his master of arts degree from Duke University and a master of architecture degree from North Carolina State University.

TRACY SHICKEL is the Director of Economic

Tracy is a connector, supporter and facilitator of regional economic development and serves on various boards committed to creating vibrant communities including UD Horn Entrepreneurship, the University Science Center Community Engagement and PHLLife Congress. Tracy holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration and Marketing Management from the University of Delaware. She can be reached at tshickel@udel.edu, on LinkedIn, and @tlshickel on Twitter.

KENDRA CHATBURN