By Andrew Lieber, Assistant Project Manager, Brailsford & Dunlavey. This article is Part 2 of a 2-part series. Part 1 is about concept insights; Part 2 is about process insights.

Part 1 of this article identified a series of innovative partnerships that could be explored to enhance a collegiate athletics facility development. Whether it’s a partnership with the municipality, private-developer, internal academic department, or anything in between, the real crux of the matter is thinking innovatively about partnerships.

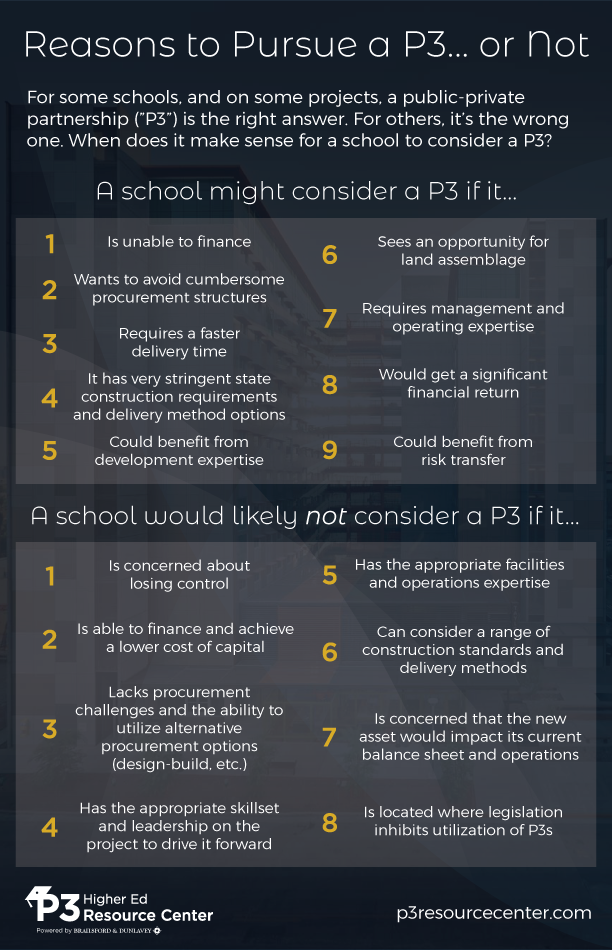

As you’ve read in Part 1 – Concept Insights, there are several potential innovative partnerships that can deliver transformative projects at your institution. You’re probably asking yourself though, “Great, but how does this take shape?” Forming successful partnerships can be a laborious and complicated process. Institutions need to be strategic about how they invest in such expensive and potentially transformative projects. Where institutions develop athletics facilities without great strategic guidance, or any guidance at all, certain aspects seem to be repeatedly overlooked or misinformed. Utilizing responses to common P3 development misconceptions as described in “Higher Ed P3 101 – Part 6: Common Misconceptions,” several process insights are examined and applied to collegiate athletics facility development.

The following insights will identify common pitfalls or challenges that occur in collegiate athletics facility partnerships and how those challenges can be prevented or overcome. These represent a more innovative approach to planning and forming successful partnerships.

Part 2 – Process Insights

PROCESS INSIGHT #1: DEFINE YOUR TRUE OBJECTIVES, THEN INGRAIN THEM IN THE PROJECT

There is a phrase commonly spoken when an institution decides not to pursue a partnership: “This could take away from our mission and core business.” On the face of it, this makes logical sense. Adding partners to a project dilutes the outcomes or objectives amongst multiple parties. However, this thought overlooks arguably the most critical phase in exploring partnerships in venues—Project Definition. Why consider a partner that does not advance or compliment your mission in the first place? If the partnership does not achieve objectives that are clearly detailed in the definition phase, it would not be considered.

While it is not groundbreaking to say the institution must clearly define objectives before entering into a partnership, this project definition process is often overlooked or misunderstood. Take a moment to imagine Institution A. Institution A is interested in renovating its football stadium but doesn’t have enough funding despite combining net new revenues from premium seating, sponsorship, augmented ticketing opportunities, donations, and department reserves. The institution isn’t sure if donations can cover the funding gap, so it decides to explore partnerships. So far so good.

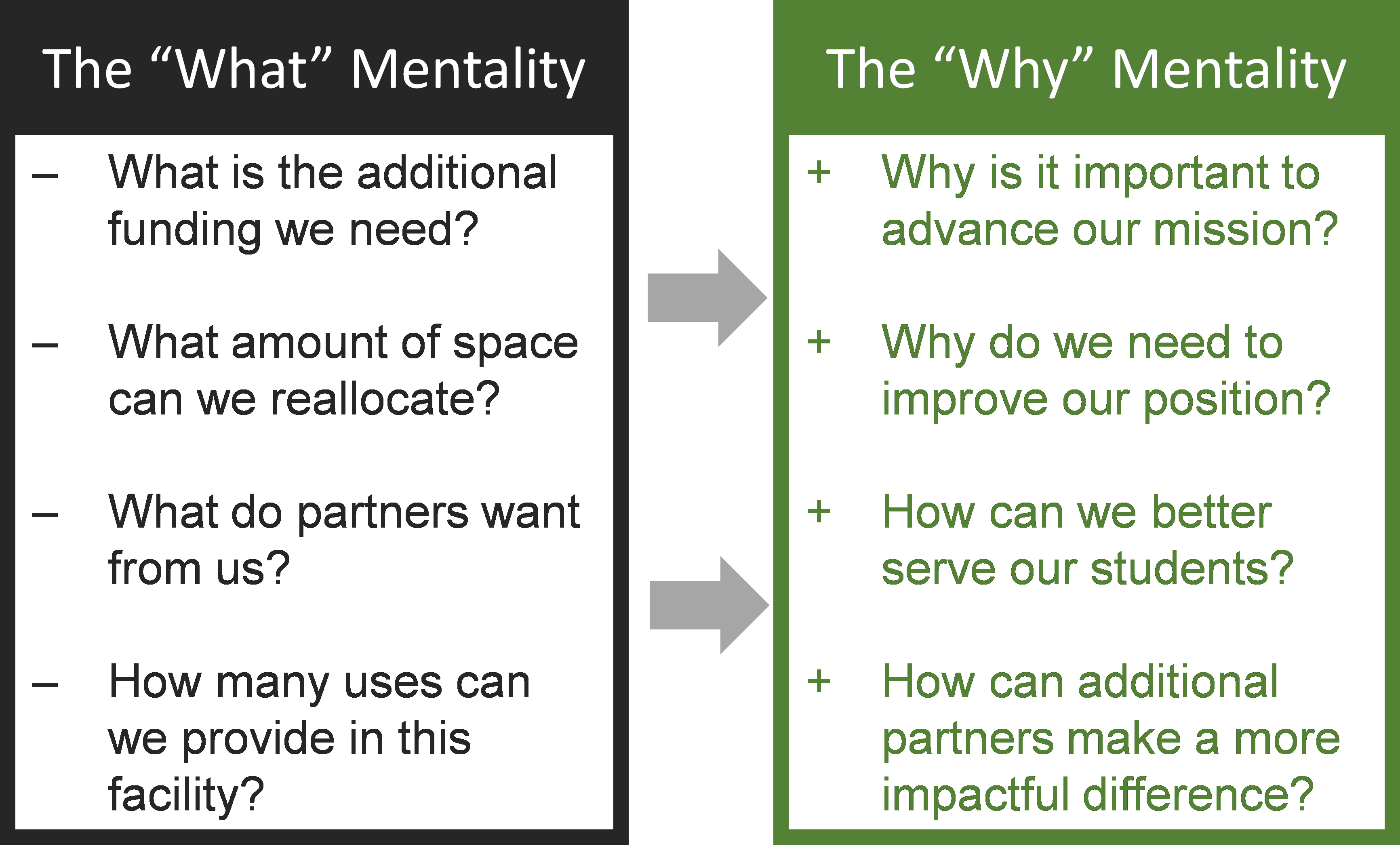

Here’s where the institution missteps: It identifies the objective for the partnership as a “What”—“What funding can we receive to close the funding gap?”

Instead of finding partners that can help answer the simple “What” questions, look at partnerships that answer the driving “Why” questions. In doing so, you’re more likely to collaborate on a transformative process.

PROCESS INSIGHT #2: GET PROFICIENT AT QUANTIFYING AND CONVEYING VALUE

While partnerships bring a lot of non-financial benefits, at the end of the day, they need to make sense financially. As an institution, you will not be able to entice a partner or agree to terms when solicited for partnership—whether a private developer, the local public entity, or some other organization—if the numbers don’t work, and if they don’t tell the right story. That means that a critical part of the exploration of any partnership is carefully and accurately quantifying and conveying the values of the project. Only once the potential partners fully understand the true value of the project can investment be committed to the partnership—whether a dollar amount or an asset associated with a dollar figure (land, tax breaks, etc.).

The professional sports world is no stranger to the importance of valuation. Let’s say there’s a minor league baseball team that wants to relocate to a new city. The team communicates the impact its presence will have on the city. There are one-time impacts, like the construction jobs during a facility build-out. There are also annual impacts, like sin taxes, new tax-paying workers that come to town to find employment with the ballpark, etc. It is not necessarily easy to determine one’s economic impact as there are so many ways a ballpark can impact its locale, but this step is critically important when setting up a partnership. Imagine that the baseball team incorrectly quantifies its value, undervaluing itself significantly; the city it’s looking to partner with will offer less of an investment. Or imagine that the baseball team overvalues itself. This could lead to a variety of problems, including time and money wasted on additional studies, eroded trust, or the creation of a project that cannot be sustainably funded as described above.

For the institution looking to partner, the lesson here is that time and effort must be expended in quantifying the project values as accurately as possible. If you cannot do that in-house, look to partner with an independent advisor that can objectively assess the partnership.

PROCESS INSIGHT #3: BE WILLING TO GIVE UP SOME CONTROL

Partnering is not the answer for every project—not even close. When two or more entities enter into a partnership, the goal is that each gets something significant:

While partnerships can be arranged to maintain as much of certain types of control as possible, it should not be shocking to hear that each party gives up some control. When a city partners with a privately owned professional sports team to construct or renovate a venue, the private owner typically retains the operating revenues from the facility and control over how the facility will operate. The municipality might retain ownership of the venue, but would have limited control on the day-to-day operations. The deal structure for the partnership agreement would outline certain aspects of operation required to meet the municipality’s needs, but they would not have total control.

Currently, we’re beginning to see an interesting situation unfold in Austin, Texas, with the University of Texas’s pursuit of a new arena and training center for men’s and women’s basketball. The University identified a need for a new arena in order to compete for new and better recruits in basketball. The University released a Request for Qualifications and Proposals (“RFP”) to the private development community to select a partner that could fully or substantially fund the development of the arena and manage operations. Given that the private developer would be substantially funding the project, they could have final decision-making power for the ultimate program and operating procedure for the facility. It’s clear that the University decided they are willing to relinquish some control of the development and operations of the facility in order to augment their athletics facilities offerings at what they expect to be a minimal capital outlay from the University.

SO WHAT NOW?

It’s clear the development world of college athletics facilities is not so linear. Developments are not necessarily single-entity nor traditional P3s—there are many different forms of partnerships that can result transformative projects for an institution. In addition, there are common hurdles that limit partnership development. A development advisor can not only provide insights into new and innovative partnerships; advisors work with institutions across the country and analyze all different types of asset developments. The great advisors ground themselves in the true driving objectives of the institution and ensure the process works to everyone’s benefit. What’s really important is thinking innovatively about partnership types and how to avoid common pitfalls that limit the potential to achieve the driving objectives.

ANDREW LIEBER is a strategic advisor on collegiate, professional,