By Andrew Lieber, Assistant Project Manager, Brailsford & Dunlavey. Bio below. This article is Part 1 of a 2-part series. Part 1 is about concept insights; Part 2 is about process insights.

I am not saying anything earth-shattering when I say that collegiate athletics departments of all sizes are financially and/or spatially challenged. Across the country, public and private schools alike are constructing and renovating facilities or expanding athletics offerings with similar objectives—recruiting athletically and academically talented student-athletes, retaining a dynamic general student population, and engaging alumni and community members for support. With more and more initiatives competing for the same pot of money to cover these endeavors, though, it is harder and harder to develop a competitive advantage, let alone a sustainable one.

Public-private partnerships (“P3s”) have repeatedly been discussed as one solution to this problem. By partnering with a private developer, for example, an institution can have a new multipurpose event center / stadium / training center built and even operated on or near campus—all with limited capital investment, depending on the deal structure of course. This would be a situation where the private developer finances the project, maintains operations, and receives many of the operating revenues, while the partner benefits from the project through utilization or other benefits. While traditional P3s are being discussed, I would argue that universities and athletics departments actually should think even more innovatively—partnerships of all sorts are worth exploring, not just “traditional” P3s. I say this because, in the sports world—my world—partnerships are not some bold new frontier; they’ve been proven many times over.

This article series seeks to offer bold concept and process insights from sports venues, central to my research and expertise, in two parts. I have studied and advised on partnerships—what they offer, what they don’t offer, how they work, where they fail, and of course what’s trending. Throughout, I’ll share insights I’ve gathered and deduced that might help your own thought process to approach innovative partnerships. Some of these insights might surprise you.

Part 1 – Concept Insights

In part 1, the following insights will identify potential partners not typically involved in collegiate athletics facilities development and why those partnerships would be successful. These represent a more innovative means to form beneficial partnerships.

CONCEPT INSIGHT #1: LOOK IN YOUR OWN BACKYARD

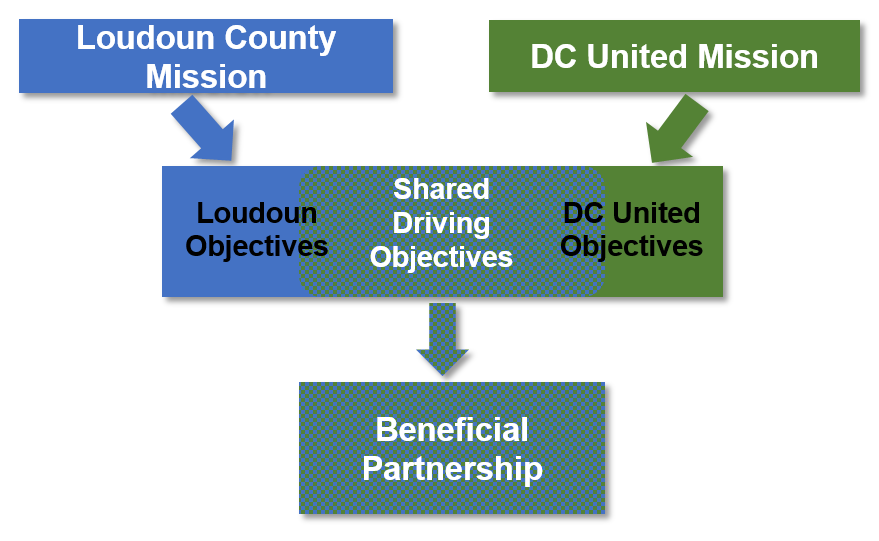

For decades now, sports teams and venue owners have partnered with municipalities. These partners have very different missions, but they have found success by identifying overlapping objectives that do not interfere with their ultimate mission.

DC United, the Major League Soccer team in Washington, DC, is one such example. The Team is planning to enter into an agreement with Loudoun County to develop a practice

It hasn’t become commonplace yet, but we’re starting to see more and more colleges and universities partner with their city—the partner right in their backyard.

A particularly salient example of this insight involves the College of Saint Rose, the City of Albany, and the Christian Plumeri Sports Complex. The College of Saint Rose, an urban institution currently competing in the NCAA D-II Northeast-10 Conference, identified a need for additional and contemporary practice and competition venues. The college, being landlocked in an urban environment, lacked space to construct new facilities. Upon learning that the City of Albany had unused fields at nearby Hoffman Park, an idea emerged: What if the college and city partnered, each offering their respective advantages (Saint Rose – donation support; Albany – underutilized and unkempt fields)? Ultimately, the Christian Plumeri Sports Complex was developed, featuring multiple fields, a variety of support structures (e.g., spectator seating, parking, equipment storage), and a community building. The college improved its athletics offerings, and the city revitalized an unused facility and so provided important, positive programming for an otherwise lacking neighborhood. For additional information on the project, see “The Place We Call Home: The College of Saint Rose’s Win-Win Partnership with the City of Albany.”

This story undoubtedly illustrates a partnership that led to a successful venture. But it’s not a P3 in the typical sense. The college didn’t lease land to a developer in exchange for a facility. The college needed something and realized that a potential partner in its own backyard—the City of Albany—also needed something, and that their needs could be not only answered through collaboration, but that the two entities could accomplish something so much greater together than they could on their own.

CONCEPT INSIGHT #2: CONSIDER SHARING SPACE

What if an entity were unable to invest in a project without a guarantee for retaining a physical asset or direct benefit? Many times public funding or student fee referendums for sports projects do not pass due to the constituents not receiving information on, or misunderstanding, how the benefits of the project relate to them personally. The allocation of public funding for sports and recreation projects (or student fees) can be controversial, but if that funding were to be allocated for activities directly tied to services provided to the tax (or fee) payers, it could then become more acceptable.

From a professional sports perspective, imagine that a new baseball team is interested in constructing a facility in town. These facilities are more than just a playing field these days—they’re planned to be true mixed-use developments with office space, restaurants, and retail. However, these facilities are mostly occupied in the evenings and on weekends when games are being played. The new foot traffic promised to the area and surrounding developers is only present for approximately 25% of the week. Surrounding developments are then limited based on this traffic pattern and curb operations, or do not develop at all.

So I’ve begun testing shared physical space with other entities, for example the local municipality. Cities generally need office space from 9am to 5pm during a traditional work-week—which is to say, not in the evenings and on weekends. Perhaps the city could own or lease a portion of the ballpark, each having offices, and each bringing enough of a workforce to the area that, together, the surrounding restaurants and retail stores remain open all day. Consistent foot traffic throughout the day generated from day-time office use in addition to the evening foot traffic for events creates a comparatively more ideal situation for ancillary development.

Sharing space can also provide opportunities for decreasing up-front and ongoing expenses during construction and operation. Permitting and construction costs get shared up front; then there are additional savings for ongoing costs throughout the facility’s lifecycle, like cleaning and maintenance through a larger competitive buying power for contractors.

Professional sports venues are not the only facilities with an ability to share space. The same could very much be true for a collegiate facility. Imagine a new athletics facility being developed on the campus edge. What if one of the institution’s administrative or academic departments or a municipal functional department partnered with the athletics department to share portions of the eventual space? A similar phenomenon would occur where consistent foot traffic is increased on a day-to-day basis. That comparatively larger daily population would require and desire additional services, inspiring ancillary development on the campus edge. Ultimately, the partners, surrounding neighborhood, and campus would benefit from this new development. The institution would also benefit from a new “front door” with constant activity.

CONCEPT INSIGHT #3: REALIZE THAT YOU CAN START A POSITIVE FEEDBACK LOOP WITH YOUR SURROUNDING AREA—AND THEN BENEFIT FROM THE LOOP YOU STARTED

In the higher education community, innovation districts are attracting plenty of attention. In the sports world, we’ve been exploring this concept for years now. When a sports venue opens in a city, the city gets not just the physical venue but an entire network of people—players and their family, the employees in the ticket office, the vendors, the janitors, the mechanical service contractors, on and on. As the city becomes more appealing through added jobs, added cultural activities, and a general energy in the air, the city benefits. Suddenly, the area is attractive not just to sports fans or professionals looking to work with the new venue, but to all employers—because the city now has this vibrant, community feel. As more and more talented workers move to the area, the benefits to the city increase. More tax revenue provides more resources. More people on streets means safer streets. More activities means happier residents. More population means more opportunities for development. A city can be transformed.

And what happens to the sports venue as it transforms the city? It becomes a vibrant corner of the city, with an increasingly large and energetic fan-base. That means more tickets sold, a better game-day environment, and more talented employees.

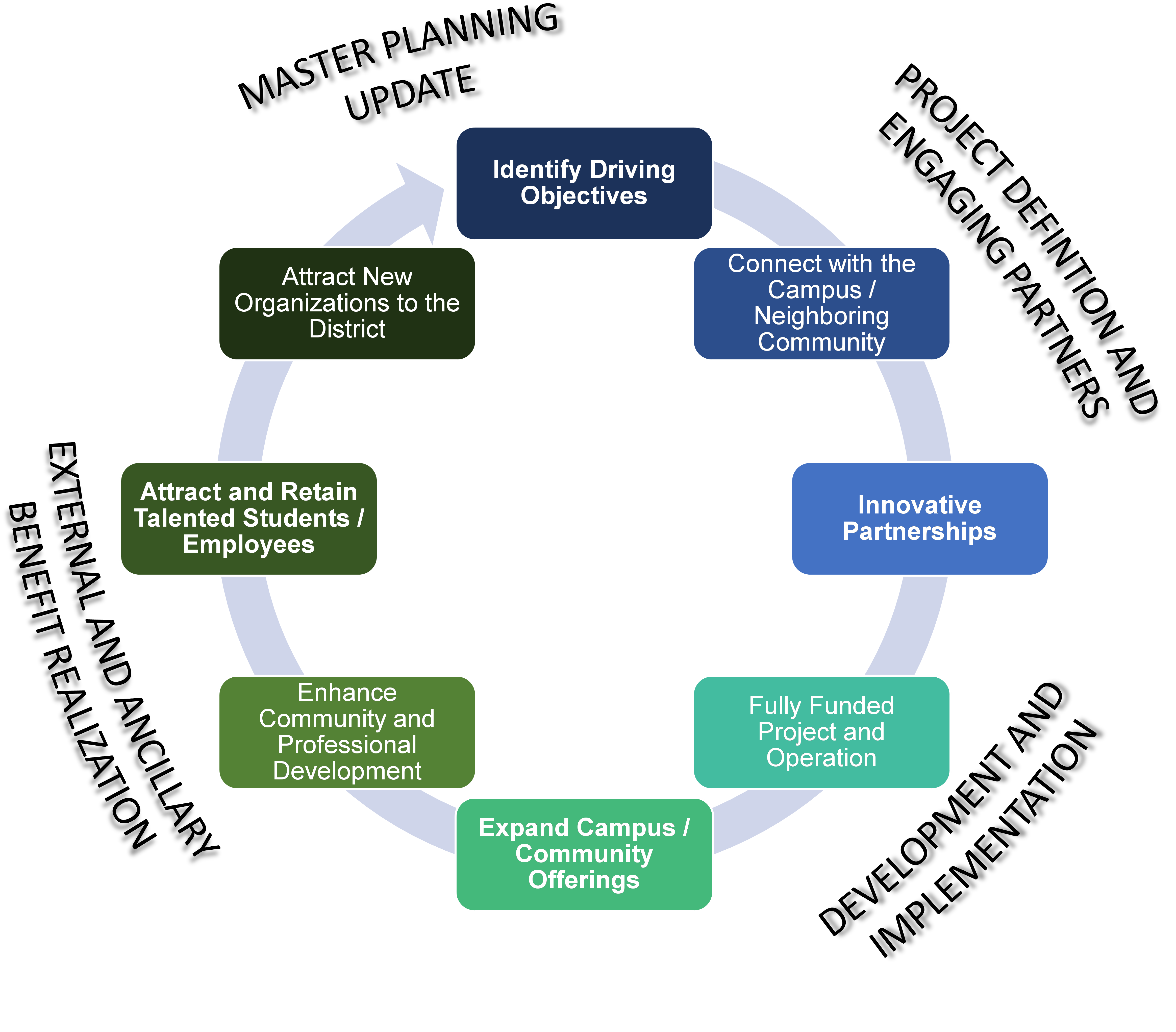

The above is a graphic illustration of this positive feedback loop in action. Beginning with clearly defined driving objectives for development in the community, the loop flows through an engaged partnerships process and facility development, into external or ancillary community benefits, and beginning again with a master plan refresh and identification of new driving objectives to maintain competitive advantages.

Higher education institutions can activate this same principal to receive similar boosts to their own recruitment and operations. Consider Notre Dame and its renovated football stadium completed as part of the Campus Crossroads project. Touted as “the intersection of academics, athletics, and student life,” this project involves, among significant renovations to the football facility, adjoining buildings to the stadium that include: a new home for anthropology, psychology, and media classrooms; a new student union center; and a new home for the music department.

Suddenly, the school is getting more than a state-of-the-art football stadium; they are able to expand four academic departments and integrate a general student life asset that drastically increases the number of students impacted. Not only does this allow the project to access donors from a larger cross section of the university than just athletics, it augments its competitive advantage for talented students. With a greater number of talented graduates coming out of the school—and graduates talented in certain areas—the region can be more attractive for employers as well. What if a project includes a research facility studying the effects of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (“CTE”) in athletes (see Arizona State University – Sun Devil Stadium), or a physical therapy center, or orthopedic surgery center? Now academic departments as well as top employers could get involved.

A key similarity for institutions here: Being located in a vibrant, employment-rich city is a great way for institutions to gain a sustainable competitive advantage

CULMINATION IN A P4

“Traditional” P3’s continue to be, and should be, considered in the right situations to develop new facilities. But, what if there’s more to be considered? Can a partnership exist combining the concepts discussed? Partnerships also do not need to fund the entirety of a project. In application, they may only be utilized to cover a funding gap. What if a public institution partners with the municipality and a private partner: a public-public-private partnership—a P4 per se?

Ultimately, though, the bigger question isn’t, “Should I partner with other organizations?” This bigger question is, “What is the right partnership for this project, if there is one, and how does this come together?”

ANDREW LIEBER is a strategic advisor on collegiate, professional,