By Joe Bosch and Dan Froehlich, Senior Vice Presidents at D.A. Davidson & Co., and Terry Gilbride, partner, Hodgson Russ LLP. Bios below.

According to the American Association of Community Colleges, 28% of public community colleges in the U.S. offer on-campus student housing. In some states, like New York, this percentage is much higher. There are many reasons why community colleges have elected to build on-campus student housing.

- To offer students “the full college experience.” Many students associate the college experience with on-campus living. Living on campus can also boost student engagement in the campus life, which can increase retention and graduation rates.

- For colleges in rural areas, student housing offers an alternative to commuting for students that already lead busy lives.

- Student housing enables athletes, international students, and other students from outside of the community college’s region to attend, which can boost enrollment and tuition revenue.

Adding student housing usually prompts colleges to make other changes to the campus culture, including becoming a “24/7” campus. This often involves building dining and fitness facilities, extending hours for existing facilities, and adding evening and weekend on-campus activities.

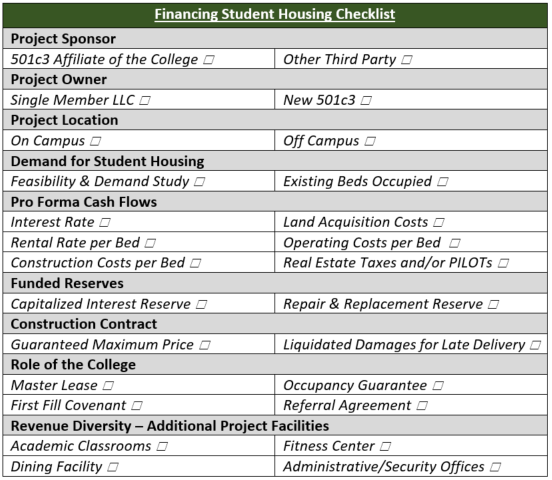

In many cases, community college student housing projects are financed using a Public-Private Partnership (P3) financing model where the public entity is the college and the private entity is a 501(c)(3) affiliate of the community college. In some ways the challenges of financing student housing at community colleges are similar to those at four-year campuses. Demonstrating pro forma debt service coverage is critical and while the cost of the debt is a significant factor in this, the other project costs are even more important to manage and control: Land Acquisition Costs, Construction Costs per Bed, Rental Rate per Bed, Operating Costs per Bed and Real Estate Taxes and/or PILOTs.

Like other student housing financings, community college projects must be structured with appropriate collateral, including a mortgage on the building, a pledge of project revenues, and adequate reserves for repair and replacement of furniture and fixtures and for maintenance.

While the fundamentals are similar, the lack of residential history at most community colleges creates skepticism among lenders and investors that must be addressed. In order to successfully attract financing for community college student housing projects, it is critical to address project ownership and project location along with two primary risks—occupancy or rent-up risk and construction risk.

Determining the Borrower and Project Ownership

From a legal perspective, the most important issues in any community college student housing project are (1) the nature of the entity that will own and operate the housing project and (2) the location of the site where the facility will be constructed.

Project Ownership

A common model for community college student housing projects involves the creation of a special purpose entity (“Project Owner”) affiliated with a campus-related foundation or auxiliary service corporation (“Project Sponsor”) that then develops, constructs, finances, and operates the housing project. This model offers a number of advantages to the community college. Most significantly, this structure enables the excess operating revenue from the housing project to accumulate outside of public budgeting and spending restrictions with the Project Owner or Project Sponsor, both of which are affiliated with the college, and this revenue then becomes available for discretionary expenditure by the Project Owner for the benefit of the college. This model also affords the college greater control over the development, financing, and operation of the project, and may enable the college to take advantage of project delivery models that are not otherwise available for public college-sponsored construction projects.

Under this model, it is typical for the Project Sponsor to form a new affiliate—the Project Owner. Project Sponsors typically pursue these projects through new entities in order to protect existing foundation and auxiliary service corporation resources, such as endowments or accumulated earnings from operations, from any liability that might result from the financing or operation of the student housing project. In addition, projects owned by single-purpose entities are often preferred by lending partners for bankruptcy protection reasons.

In nearly all instances, foundations and auxiliary service corporations are nonprofit corporations with federal 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status. Because the provision of housing for college students typically falls within the approved 501(c)(3) tax-exempt purposes of the Project Sponsors, most foundation/auxiliary service corporations seek to imbue their affiliates, the Project Owner, with similar tax-exempt status. This can be done by either creating a separate new nonprofit corporation and securing a 501(c)(3) exemption from the Internal Revenue Service or creating a new limited liability company of which the Project Sponsor is the sole member. The Internal Revenue Service disregards the separation between the limited liability company and the Project Sponsor and confers the tax-exempt status of the sole member upon the limited liability company. Critically, this enables the Project Owner to qualify for qualified 501(c)(3) tax-exempt bond financing. A word of caution, though: If a limited liability company affiliate is utilized, not all local real estate taxing jurisdictions treat LLCs the same way as nonprofit corporations for real property tax exemption purposes.

Project Location

Experience shows that projects constructed on college campuses have a better chance of long-term success than projects that are located off-campus. In addition, on-campus projects also have the advantage of free or very low land acquisition costs, which significantly helps with project economics. If possible, therefore, assuming a community college has undeveloped land on its campus that could support the proposed student housing project, some effort should be devoted to determining whether or not the college has the inherent legal ability to enter into a long-term ground lease with the Project Owner. A long-term ground lease is necessary to give the Project Owner (and its financing partners) site control and collateral rights with respect to the project cash flow that is necessary to secure project-based financing. For underwriting purposes, these ground leases need to be at least five or ten years longer than the expected amortization of the project financing to protect the financing partners against negative financial repercussions of a default at or near the end of the amortization period. This typically results in a ground lease term of at least 35 or 40 years with a project debt amortization of 30 years.

This is not to say that off-campus projects are not desirable or feasible. Many successful P3 community college housing projects are constructed on parcels of land that are off-campus but located in close proximity to the college campus. The development of P3 housing on an off-campus site, however, implicates a host of other issues that need to be factored into the structuring of the project, including issues related to safety, security, and real property tax exemption. In terms of campus security, since an off-campus student housing project is not technically part of the campus, college security officers may not have jurisdiction over or the ability under collective bargaining agreements to deal with off-site safety and security issues. In regard to real estate taxes, because the underlying real estate for an off-campus housing project is not owned by the community college, the project may not qualify for an exemption from real estate taxes and assessments, which can significantly burden the cash flow for the project. Additionally, while not unique to off-campus projects, it needs to be determined whether the local governmental authorities have jurisdiction over land-use matters and construction permitting for the project. Compared to an on-campus development, an off-campus P3 student housing project is more likely to be subject to local governmental oversight and control of land-use and construction related issues.

Managing Construction and Occupancy Risk

The initial risk profile of a new, unbuilt community college student housing project is much riskier than after construction and stabilization have occurred. From the perspective of attracting financing for the project, it is critical to manage and bound the risks associated with the construction period, including construction delays and costs overruns, and the risks associated with occupancy and filling the beds.

Bounding Construction Risk: Security for Creditors & Investors

Lenders and bond investors will require that Project Owners select developers or general contractors with the financial resources sufficient to enter into a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) Construction Contract whereby the contractor bears the risk for project cost overruns. These contracts also should include liquidated damages for late delivery of the project so that the Project Owner will have the financial resources necessary to house students at alternate locations until the project is completed.

In addition, it is often advisable to fund a Capitalized Interest Reserve Fund for the construction period plus an additional six to twelve months. This serves two purposes. It further bounds construction risk by providing a source of funds to pay debt service even in the event of a construction delay. If the project is completed on schedule, these funds help to ameliorate the risk of lower-than-expected initial occupancy.

Establishing Demand: Addressing Occupancy Risk

Many community colleges do not have a record of offering student housing and, as a result, it is critical to establish that there is demand either for adding student housing to the campus for the first time or for adding additional beds. The two most important components of establishing demand are (1) working with a development advisor that can help navigate all of the early aspects of the project, including a market study, and (2) determining the occupancy level for existing beds (if any).

A college can also play a role in shoring up demand for new student housing beds by entering into one of the following agreements, which are listed in order from most to least credit support for the project:

- Master Lease – college leases all of the beds and assumes the full risk of renting them to students

- Occupancy Guarantee – college agrees to lease any unrented beds up to a minimum occupancy level

- First Fill Covenant – college agrees to refer students to a particular residence hall before referring students to any other residence halls

- Referral Agreement – college agrees to refer interested students to a particular residence hall

While the majority of U.S. community colleges do not have on-campus student housing, many community colleges have successfully financed and currently operate student residence halls on their campuses. These projects enhance the student experience for many students and also help colleges to attract students from a broader geographic area. In addition, when conceived of and operated properly, student housing projects can be a good revenue source for colleges at a time when community college budgets continue to be under pressure.

JOE BOSCH (photo: left)

TERRY GILBRIDE